Reminiscences of an Early Day Lineman

by Linda Peterson

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", February 1977, page 7

(This story about Fred Koehler is copied from the June 1974 issue of Pacific

Telephone Magazine under the original title "Those were the days, my

friend.")

Ahh, the roaring twenties -- bootleg gin, flappers and oh, you kid! The world

was young, America had emerged relatively unscathed from World War I, men were

men and women were... interesting.

One man who remembers the way it was in the telephone business, and who did

his own share of roaring in the twenties is Fred Koehler. Fred retired in 1963

as district construction superintendent in Fresno after 47 years of telephone

work.

He's an insulator collector extraordinaire, as well as a veteran telephone

man. Since many of his insulator-collecting colleagues don't have the skinny on

the old days of the phone business, they besieged Fred with requests to put

together a history.

He obliged, and the result was a notebook binder filled with history,

memorabilia, snapshots, and anecdotes about the phone business in the early

days, and Fred's association with it. It's our privilege to share some of Fred's

reminiscences with ptm readers.

Fred came to work for Pacific Telephone in mid summer, 1918, in San Diego. He

brought with him a couple of years of experience as a lineman with the Home

Telephone Company and the San Diego Gas and Electric Company.

He says, "It's hard to believe in this day and age that there wasn't any

transcontinental service before the year of 1915, but there wasn't. It you

wanted to send a message east, you either trusted the U.S. mail or you sent a

telegram."

Fred's book focuses on those years of great adventure in the telephone

business, between 1920 and 1930, while the industry feverishly built open wire

lines for long distance service.

Says Fred, "It was a great day when the transcontinental line went into

service. You could make a call to New York from San Francisco for $15.00."

Right from the start, when Fred had his first job with the Home Telephone

Company as a lineman, his ambition was to be a "boomer." He explains,

"Boomers didn't always come from a ripsnorting mining community. The early

day telephone, telegraph and power linemen who went from one job to another or

from one job to another or from one company to another were dubbed floaters or

boomers. They were top hands and went wherever they could get work."

Being a boomer was more than an occupation, it was a state of mind. "A

boomer was the kind of man no one could push around. He drank his liquor raw,

liked his women soft and pretty, and he asked no favors of anyone."

My first line truck, a 1912 Autocar, that hit 15 mph!

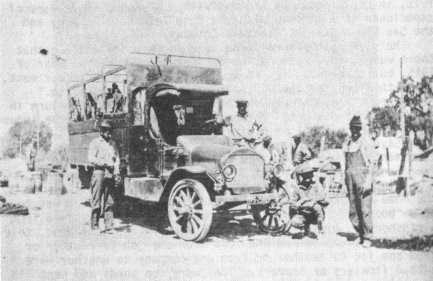

1915 Mack truck, near Paso Robles in 1918.

But the boomers were an endangered species, and progress and World War I just

about put an end to their way of life. "After the war, some of the old-time

boomers retired, some others stayed on, but companies began changing their

hiring practices. Another species became extinct."

Koehler's story picks up in the year 1920 when telephone service and

facilities were in great demand. He explains, "Radio broadcasting networks

were coming into the picture, carrier circuits were making progress and all

required more circuits. The old iron wire lines were not suitable to handle the

new circuit requirements and they had to be replaced. And, the available copper

circuits needed a lot of work. All these projects required the building up of

large line crews."

Jobs were plentiful, according to Fred. "All qualified linemen around

were hired, and still more were needed, so large groups of young men were hired

and trained."

In the next 10 years, Fred worked on a number of open wire jobs from Los

Angeles to San Diego, to Yuma, Arizona, to San Francisco, and from Sacramento to

Reno, to Wendover, Utah, and back to Ely, Nevada.

The work required a variety of equipment and no sleek, yellow, white, and

blue vans were yet available. "We used horse wagons, trucks, engines with

flat cars, and sleds. I should mention that sled was man-powered, though the

snow in the mountains might be 10 feet deep."

And, as the demand for more and more facilities kept growing, the crews had

to contend with merciless Mother Nature "Winter storms, summer and fall

fires, floods -- all caused open wire line failure that required many hours in

overtime to get the lines back in service."

Though working on the floating line crew was a rough life, it obviously had a

great deal of appeal for an adventuresome soul like Fred.

"Sometimes our work took us 30 to 50 miles from any town, so we set up

large canvas tents for sleeping, eating and cooking quarters. The heating system

during the winter was usually a pot-belly stove that burned wood or coal."

Sometimes the accommodations were a little classier. "On the large jobs

in Nevada, camp trains were built on railroad cars, which were cabins

constructed on a wagon frame."

Although the work was hard, the sporting spirit would crop up whenever there

was an opportunity. In addition to being a lineman, Fred "Kid" Koehler

was building up quite a reputation as a boxer. One newspaper account of a bout

(which he won, of course) between him and another pugilist from Fresno reads:

"It is in the consensus of opinion among the fight followers that this

was the best bout ever staged in El Centro. The two boys, evenly matched and

ever eager to mix, exhibited wonderful stamina and their ability to give and

take regular he-man wallops won the hearts of the fans and aroused their

enthusiasm to such a pitch that towards the end of the contest the house was in

one whale of an uproar."

Koehler's line crew stringing wire Sacramento to Reno, 1926.

1935, near Weed, on new route for transcontinental.

Some of the crew's recreation was a little more peaceful. "We always

looked forward to Saturday night. Almost every town had a big dance which

brought together the townspeople, cowboys, farmers and telephone hands. Everyone

seemed to have a great time and the dance would carry on to the wee hours of the

morning."

Frolicsome as the night before might be, the athletes on the crew would still

be ready for yet another tradition the following day. "Most every town had

a local baseball team, and many of the telephone men were good ball players. The

games were usually played on Sunday and the town's folks really turned out to

back their team."

Pranks were also an important part of the line crew's life. Fred reminisces

about one. "It was the habit of the big boys in Los Angeles to send someone

out to the field to be a crew's field clerk, if they were grooming him for

bigger things. One time they happened to send us a rather sissified

fellow."

Woe to the city slicker! As Fred tells it, "I'd been out quail hunting

one day and I came across a rattler. One of the other guys caught it and put it

in a can. He pulled the fangs out of it, which made it harmless. Then, before

this sissy field clerk came to bed, the joker sneaked into his tent and put the

defanged rattler in the bottom of the clerk's bed.

"It happened that I shared the tent with this poor fellow, and I heard

him come in, get undressed, and get into bed. Next thing I knew, he let out a

war whoop and ran out of the tent in nothing but his shorts. We finally calmed

him down enough to tell us what happened. Well, the company got wind of this

incident and that was the end of the instigator."

Getting ahead in the business was a little different procedure in those days.

On-the-job training was the order of the day, and a fellow with a curiosity to

learn more had to go after the learning on his own. "When I started

out," says Fred, "the boss was the boss. He told you what to do, you

were the workman and you never saw the specifications of a job."

But, youthful resourcefulness will always find a way. "We were doing

camp jobs then, and I used to sneak into the boss's tent and take the specs out

and study them and make notes. Nobody could figure out how I knew so much. Maybe

it wasn't honest, but you had to get your education yourself, in those days, the

hard way."

For luck, most crews had a mascot, usually a dog. But one crew, Fred

remembers, had a billy goat for a mascot. "He'd ride on the cab of the

truck, as if he owned it."

Working in the field often gave the men a unique look at the upper crust.

"When I worked a crew in Hollywood, the stars would leave us a pair of

slippers by the door, so we wouldn't come messing up their fancy carpets with

our boots. It wasn't just us, though, the iceman, the plumber -- whoever came to

call -- had to give up their boots."

Fred also remembers restringing line at the Hearst hideaway in Dunsmuir on

the McCloud river when the family was ready to come up after the snow melted.

"They always invited us in for lunch," he recollects. "They had a

lot of chicken, I remember, and seems to me we got a lot of backs and

wings."

Fred's fondest memory of the "good old days" was working as a

foreman in Nevada. "I was a pretty good shot, so I'd go out and get wild

game for the whole camp and we'd have a big blowout. And, there were all these

mineral springs around, nice and hot. We'd just drive up, pull off our clothes

and take a bath."

Working in Nevada had its drawbacks, however. "Some of the places we

were working were 'dry.' But, somehow, in one location, the guys on the crew

were getting the stuff from somewhere. They were coming to work pretty loaded

and the camp foreman told us to find out where that stuff was coming from.

Someone gave us a tip, and we found this old-timer who had tunneled way back in

the mountains and he was making moonshine where the creek ran through. We worked

out a little compromise with him. We promised not to tell the authorities if

he'd stop selling to our guys. Since we moved on shortly after that, it wasn't a

real hardship on anyone's side."

But, camp trains and the days of open wire lines were numbered. Construction

slowed considerably early in the thirties when the depression gripped the

country. And, after the economy cranked up again in the mid thirties, buried

cable came to the forefront.

As Fred explains, "Open wire did have a final fling when, at the request

of the United States government, an expedited line was built between Los Angeles

and Portland."

Though the thirties signaled an end of one era in the telephone business and

Fred's career, it did open another. In 1932, a perspicacious hotel owner in San

Andreas introduced Fred to another of his guests, a young schoolteacher named

Catherine. "I guess he figured a ball player as good as me would be quite a

catch," says Fred. Catherine must have figured the same, for they were

married later that year.

Forty-one years later, they're still together in the same house they

purchased when they first moved to Fresno in 1941.

Although Fred can't resist regaling visitors and fellow insulator-collectors

with some choice stories from the old days, it's obvious that he and Catherine

live very much in the present.

Fred still hunts small game and Catherine goes with him. She doesn't shoot,

but she's good company.

And, Fred still carves, a boyhood hobby he developed when he needed duck

decoys and decided to make his own. And, both are insulator buffs, and the

various shows and sales they attend all over the country have given them

frequent opportunities to travel.

Home is still Fresno, a sunny house full of insulators, carvings, flowers,

memories and two lively people undaunted by age and circumstance.

Their backyard is full of fruit trees, birds waiting in line at a

homemade feeder, and lavishly blooming rosebushes.

This writer left the Koehlers' loaded with grapefruit, a wood carving of a

friendly donkey, and a couple of insulators to launch us on our own collection.

Though we missed the "good old days" of the business, we feel we

shared in them just a little, by spending a morning with Fred and Catherine

Koehler.

|